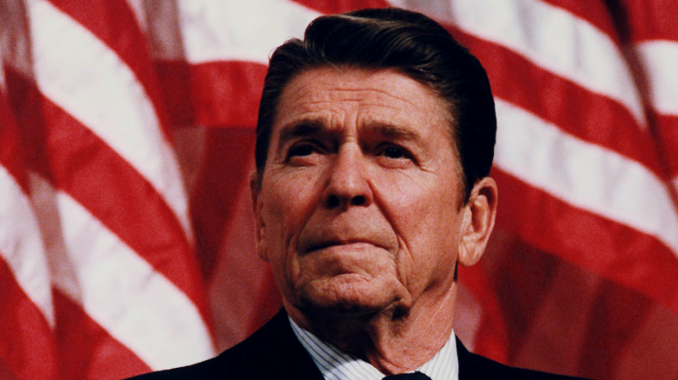

For conservatives of a certain age, the Republican par excellence was, and like shall always be, Ronald Reagan. He was not perfect, he made a number of errors in his eight years, at times his beliefs conflicted with one another, but that doesn’t matter. What made Reagan such a paragon of conservatism was his ability to articulate simply the principles of limited government, or private initiative, of American exceptionalism, all in a kindly, avuncular way quite at odds with the confrontational tone of today’s politics. Not that he was never angry, he could voice righteous indignation at time, especially when denouncing the ills of communism, but by and large he saved his wrath for the truly massive evils, giving fellow Americans the benefit of the doubt, treating even his most ardent opponents as mistaken rather than villainous. Because of this reputation, as the exemplar of the conservative, and presumably Republican, ideal, Reagan has become for many the ideal against which future candidate are measured.

However, in view of recent elections, as well as many trends in the decade preceding, I have come to ask, does that make sense? Is Reagan really the high water mark for the GOP? Or is he a fluke, a break with GOP traditions, an aberration? In short, is Reagan conservatism really Republican conservatism? Or does the history, and present, of the GOP suggest movement in some other direction?

I suppose it is easiest if we go back to the beginning and look at the GOP as it was formed. Granted, that is not always a good guide — after all the Democrats started out as a small government, federalist party — but even if there have been tremendous changes the history of those changes can inform as well.

The general public mostly seems to know the Republican were the “party of Lincoln”, opposed to slavery, which in some ill-defined way replaced the short-lived Whig Party. But for most who don’t have much interest in history, between the end of the civil war and Theodore Roosevelt, the GOP largely disappears, their beliefs understood in a hazy way at best. Not that the GOP was lacking representation, they held the presidency through several post-Civil War terms, the office holders are not particularly noteworthy, nor particularly active. Perhaps this is why the history between the Civil War and turn of the century is taught in high schools in terms of industrialization, immigration and growth of cities, and why so many have no real idea of what the Republicans believed. (Or the Democrats for that matter.)

By and large, the Republican-Democrat opposition of the 19th century was just a continuation of older party systems, with a few variations. Like the Whigs and Federalists the Republicans favored centralization over federalist distributed power, most notably during this period in terms of widespread banking regulation. Also like the Whigs before them, the Republicans were in favor of inflationary “soft” currency, both in printing of paper notes and switching from relatively stable gold to depreciating silver. And, once again following the lead of the Whigs, the GOP favored protectionist measures, from tariffs to subsidies. Where the GOP came into its own was in two beliefs it adopted in the later 19th century, nativism* and prohibition. The Republicans were not the first to oppose immigration, but they were more ardent about it than preceding groups, to a sufficient degree that many late-arriving ethnic groups — Irish, Italian, Jewish, Polish — embraced the Democratic party well into the second half of the 20th century. On top of this, the Republicans also embraced the evangelical movement of their day, the temperance and prohibition movements, fighting to end the distribution and consumption of alcohol. There were a smattering of other issues, but by and large soft money, protectionism, nativism and temperance give a good feel for the Republicans of the 19th century.

This was the Republican Party as it existed until the turn of the century. In 1890s the Democrats had joined with the Populist party and take a turn away from its old beliefs, small government, federalist, hard money Democrats having their swan song in the disjoint pair of Cleveland administrations. Given the two party system of the US, it was unlikely such a dramatic change would pass with the Republican responding, and the GOP did see a brief period of “reform Republicans”, culminating in Roosevelt and his Bull Moose Party. But, while the Democrats were forever changed by their merger with the Populists, it seems the Republicans held on to very little from this period. Having never been proponents of laissez-faire government, the idea of intervention and regulation was nothing new to the party, and so this period seemed to have less influence on the Republicans than the Democrats, and the GOP entered the 1920s largely holding the same beliefs they had in the 1890s.

The 1920s were the heyday of Republican policies**. Using the new Federal Reserve, it was easy to enact an inflationary “soft money” policy, while new tariffs were used to enact protectionist ideas. Even the temperance movement saw a victory in the constitutional amendment enacting Prohibition. Though often portrayed in popular history as an era of hands off, laissez-faire, there was definitely a tendency toward a neo-mercantilist, protectionist policy. Business received various privileges and subsidies, trade was controlled via tariffs, and credit was kept largely low interest through monetary manipulation, including large infusions of cash through public building projects. There were also tax cuts for corporations, which seems to be a common phenomena of protectionist administrations. And, as we also see in many protectionist administrations, there were allegations of favoritism, cronyism and corruption.

Following the start of the Depression, the Republicans were somewhat in disarray. On a state level they largely remained the party they had always been, but repeated defeats on a national level brought a degree of soul searching and change. In 1936 they ran Alf Landon for president, something of a throwback to the old “Reform Republicans”, likely to try to counter the popularity of Roosevelt’s various reforms, and in 1940 repeated the effort with Wendell Wilkie, who, except in his isolationism, was also more liberal than the rest of the GOP***. But by 1944 the GOP seemed to have found its bearings once again, and ran a fairly traditional “conservative” GOP candidate in the form of Thomas Dewey. Granted, Dewey had enacted some “liberal” reforms in New York, and immigration was largely a non-issue during wartime, Dewey seemed otherwise to stay pretty close to traditional GOP concerns, both in 1944 and 1948.

In the post-war years, the GOP underwent some changes, but much of the original GOP platform remained. Temperance was by and large a dead issue since the 1930s, but drug prohibition and, in the latter part of the century various moral crusades under the growing evangelical movement, came to replace banning alcohol as the party’s moral crusade. Societal norms made the sort of nativism the party had pursued in the 19th century less and less acceptable (at least until modern times and the rise of the “alt Right”), but opposition to immigration continued simply in less condescending terms****, though its importance as an issue would wax and wane over the years. Otherwise, Republicans continued to promote a platform quite similar to that of the 19th century, promoting protection of industry, subsidies for select businesses and a soft credit policy.

At the same time the GOP was returning to a largely “business as usual” policy, some within the party were adopting a different set of beliefs. Arising from that laissez-faire minority that had existed within the party for some time, it found its expression in Goldwater, and later Reagan. Based firmly on principles more akin to the original Democrat platform than that of the GOP, it embraced smaller government, more individual liberty and a federalist approach to government. Granted, it never quite threw off all the baggage of the GOP. Reagan’s ties to more intrusive, big government religious groups, for example, or the failure of any Reagan-era Republicans to even begin to address monetary concerns, these show that even as they turned their back on the traditional GOP these individuals still kept a few ties. But, by and large, Goldwater, Reagan and their ilk represented a considerable change from, if not a total break with, the old Republican Party.

What has come since suggests that since Reagan the party has been more and more reverting to its old ways. The elder Bush was largely locked in to following the policies of Reagan, but since then — excluding the abortive “Contract With America” which was something of a Reaganite last hurrah — the GOP has become quite comfortable with tariffs, subsidies, government spending, intervention of all sorts, and subordinating concerns with small government to appease the growing evangelical movement. And, of course, with the triumph of Trump and his explicit protectionist, neo-mercantilist policies and implicit embrace of the racist alt Right, it is hard not to see a return to the GOP as it had been throughout most of its existence.

Which leads me to conclude, though Reagan had tremendous influence during his time in office, enough to even decide many congressional elections in 1994, and though Reagan is remembered fondly by many, his presidency, far from being the pinnacle of Republican policy, was instead an aberration, a deviation from the flow of GOP policy from its foundation. “Conservatism” as the term was used by Reagan and Goldwater and Buckley and others is not really the overall policy of the GOP, and the fact that, for a time, the two came together is more of a fluke than anything else. While many in the GOP may continue to praise Reagan, the policies they support drift ever farther from those he espoused, as the GOP moves away from the detour which was Reagan and returns to its original course.

—————————————————————

* Nativism was clearly not unique to the GOP, the KKK in the south was Democrat. But then again, everything not brought into the state from the outside was Democrat, so that isn’t exactly meaningful. All native born teachers were Democrat, so were all bakers and all people arrested for assault. The South simply WAS Democrat, so the KKK being Democrat is less significant than some suggest.

** When speaking of Republican policy in the 20s it is largely a matter of congressional action. Until Hoover began to see things collapse, the presidents of the era were not particularly doctrinaire Republicans, and congressional action had far more influence than the presidents. It is also worth noting Coolidge was a bit of an aberration, less inclined toward subsidies and protection, more liberal on immigration. He also had far fewer scandals than either his predecessor or successor.

*** When I speak of “liberal” and “conservative” in terms of mid-20th century Republicans, it is not exactly the terms as used today. There were some laissez-faire Republicans (as Dewey argued in a speech in 1949(, but they were a small minority. The “conservative” wing was largely neo-mercantilist, favoring protectionism to benefit industry, while “liberal” favored some measure of pro-labor reform and favored protectionism for both industry and labor interests. Very few in the GOP of this era advocated for less government intervention.