Steve Ditko passed away on June 29, at age 90. He was the “third man” of the triumvirate who created the modern Marvel Comics, along with Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Ditko was an artist, and while he didn’t co-create nearly as many iconic characters as Kirby, he was responsible for Spider-Man, most of Spider-Man’s most famous villains (like Doctor Octopus, The Vulture, The Sandman and The Lizard), Doctor Strange and associated characters, much of Daredevil’s original look and possibly Iron Man (claims of character design have been attributed to both interior artist Ditko and cover artist Kirby.)

A disagreement with Stan Lee inspired Ditko to leave Marvel. He’d started out at another company, Charleton, and returned to working for them full-time. At Charelton he created Captain Atom, The Question, the modern incarnation of Blue Beetle and others.

The dominant superhero comic company in that era, however, was DC. As the 1960s progressed, Marvel took an ever-deeper cut of the superhero comic market. DC decided to take advantage of Ditko’s availability and let him create some of his own characters. This led to the new comic Beware… The Creeper! (starring The Creeper) and the characters of Hawk and Dove, before Ditko went back to Charleton exclusively.

That exclusivity didn’t last long. Through the 1970s, 1980s and into the 1990s Ditko worked at both Marvel and DC intermittently (although at Marvel, only after Stan Lee had left his post as editor-in-chief.) He created or co-created Machine Man, various Micronauts characters, Speedball, Captain Universe and Squirrel Girl for Marvel; he created Shade, the Changing Man, Stalker and Star-Man for DC comics.

Oh, and he also helped create The Watchmen and Vertigo Comics. Kinda.

In the 1980s, Charleton Comics was going into bankruptcy. The success of Marvel and DC had squeezed Charleton out of the supermarket and corner store comic racks, and there were very few comics stores in existence. Charleton’s assets were acquired by DC, in an effort to keep another company from revitalizing the characters and creating more competition.

DC also had Alan Moore. He was their star, the man who’d taken Swamp Thing and made it into a comic that literate adults read and discussed. When he heard that DC had gotten Charleton’s assets he pitched an idea for a 12-issue limited series addressing the nuclear fears of that time, as well as issues like the Vietnam war and rape survivors. It would star the Charleton characters, which DC didn’t even care about – they were planning to retire them – and would kill off some of them in spectacular ways.

Moore wrote the series… and then DC reneged. Someone on the publishing side of Warner Brothers (DC’s parent company) thought the Charleton characters could be revitalized by DC in the future. Moore was furious, but the script was already well in progress. He modified characters on the fly – The Question became Rorschach, Blue Beetle became Owlman, Captain Atom became Dr. Manhattan – and the Watchmen was back on.

Moore, however, was furious. Having his authorization to use the characters pulled helped convince him to leave DC. It also became a key reason for new contracts in the comics industry, where creators would retain some of the rights to the usage of characters they created. Those new contracts were the launching point for the new Vertigo line of adult-targeted comics from DC.

Ditko, however, saw no reward for this (or, really, for Spider-Man, Doc Strange, The Creeper, The Question or anything else he’d made). When he did attempt to reap a reward, it was by starting his own comics company, Defiant, in the early 1990s. He used the hype associated with the perceived boom in comics-as-investments and “alternate covers” to create two comics, Warriors of Plasm and Dark Dominion. They had the hook of having prequel issues available in trading card packs, where assembling a full set of the cards would result in a full comic book. The gimmick failed, and the comics quickly died out.

All of that is his professional impact, which is considerable both to the comics medium and pop culture in general – much of the world knows Spider-Man, for example, and many know The Watchmen – but he was famous inside the industry for personal reasons as well.

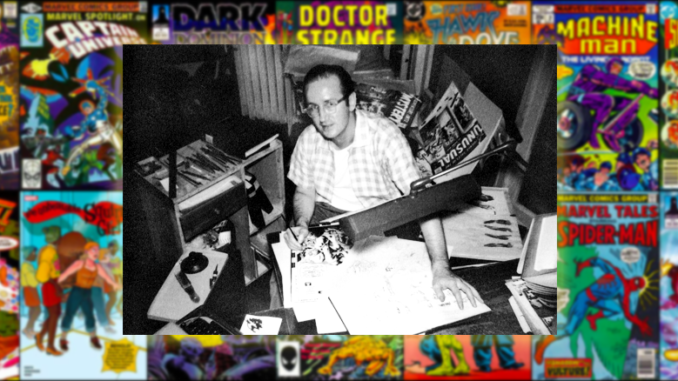

Nobody saw Ditko.

He didn’t do publicity shoots. He didn’t give interviews. He didn’t attend conventions or go to receive awards. He preferred to let his work speak for him and thus built a mystique about himself for younger artists who’d grown up imitating his work.

He was also a devoted objectivist, a Randian whose viewpoint came through in some of the comics he wrote. He never attempted to hide that position, even in a industry where any flavor of traditional conservative philosophy is often unwelcome.

In 2007, the BBC made a documentary about the comics legend where Jonathan Ross went hunting for him, In Search of Steve Ditko. It seems an appropriate way to end this piece.