Trying to find Crush, Texas on a map would prove to be impossible today, and at most times in Texas history. For about a week in 1896, it was one of the most popular cities in the state.

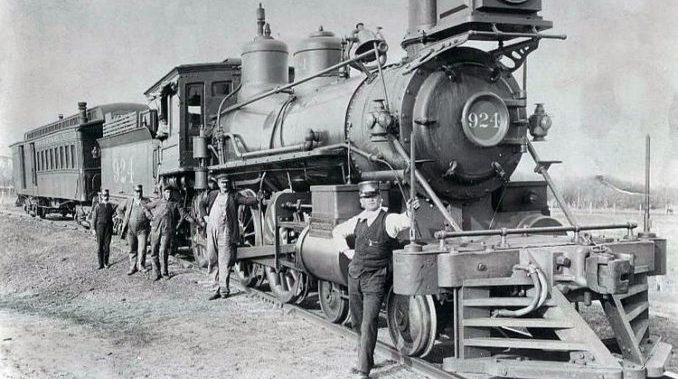

Crush was named after its founder, William George Crush, a passenger agent for the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad Company. The company was popularly known by the initials of two of its locations, “K-T”, often pronounced “Katy”. The Katy Trail retains a prominent place in North Texas history because of its extensive reach throughout the area, even though it has long been out of business.

But in 1896 the company was thriving, and Crush had an idea for a great promotion to further encourage passenger train use. An offer was made for people to get round-trip tickets from anywhere in the state to Crush and back for a mere $2… and while they were in Crush, they could watch the event.

The event was the crash at Crush.

Two full-sized steam locomotives were going to get up to a top speed of around 50 miles per hour and then smash head-on into each other.

The promised spectacle was a great lure. During the few days that Crush was in existence, more than 40,000 people (almost 2% of all Texas citizens) congregated there for the event. Water wells had been drilled, telegraph offices erected, lodging arranged, food vendors and carnival performers alike had come to serve the crowds. There were even 200 policemen who had been hired to keep the peace.

A minimum safe distance from the exact crash site was determined to be less than 100 yards, so press were given a strict 100 yard boundary from which to take photos and report. Out of an abundance of caution, other viewers were restricted to a full 200 yard distance. Still, that was close enough to get a great view of the collision.

What Mr. Crush and the Katy Railway Company didn’t consider was the fact that both of the engines had highly pressurized boilers. To be fair, they’d consulted a number of engineers and had been assured by most of them that all was safe. To be even more fair, the one dissenting voice had informed them specifically that the damage from a high-speed crash would likely rupture the pressurized boilers… which was exactly what happened.

When the two locomotives collided, the expected noise was joined by the explosion of both boilers, which sprayed superheated water and threw shrapnel into the crowd. At least two people were killed. Dozens reported injuries, including a photographer who lost an eye to a hurtling bolt.

William George Crush was fired that night, and the town was torn down expeditiously.

The next day, his fortunes reversed again. Despite the casualties, attendees had rushed the crash site to seize souvenirs and tickets for future passage on their line were up dramatically. Crush was re-hired, with his first task to contact the injured and the families of the dead and negotiate compensation. Using both cash and promises of lifetime passes on the Katy lines, he successfully managed his task and remained with the company until he retired after 57 years of work. The event proved to be such a success that others took up the mantle and arranged their own staged locomotive crashes until the mid-1930s, when the waste of it all drove the events out of fashion during the Great Depression.

Question of the night: have you ever been witness to (or participant in) an accident or disaster?