The state of the art of medicine in the mid-nineteenth century was such that doctors were still relying on the four humors of Hippocratic Medicine to explain and treat illness, an archaic outlook that dated back to approximately 450 BC. Physicians in 1850 had no concept of microorganisms, or how disease was spread.

Ignaz Semmelweis was born in 1818 in Buda (now part of Budapest), Hungary, of German ethnicity. The son of a wealthy merchant, he began studying law at the University of Vienna but shifted to medicine, graduating in 1844. By 1846, he was employed as assistant to the head of Obstetrics at Vienna General Hospital, which was essentially a teaching hospital that catered to the poor. He supervised and taught students, examined patients, assisted with difficult births, and kept records.

A common cause of death at that time among women who had just given birth was puerperal fever, also known then as childbed fever. We know now that it was sepsis caused by Group A hemolytic streptococcus, a bacteria.

And a miserable end it was: raging fevers, putrid pus emanating from the birth canal, painful abscesses in the abdomen and chest, and an irreversible descent into an absolute hell of sepsis and death — all within 24 hours of the baby’s birth.

Dr. Howard Markel

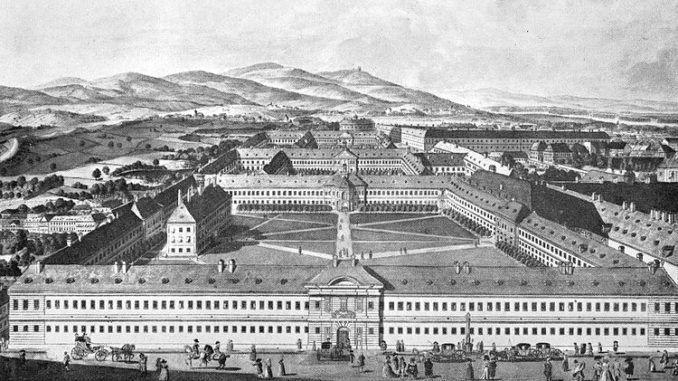

The hospital had two maternity clinics, each with its own maternity ward.

Doctors and medical students (all of whom were men) staffed the first ward. Midwives (all of whom were women) staffed the second maternity ward.

Semmelweis observed that the number of puerperal fever deaths was three to five times greater in the doctor’s ward than in the ward attended to by midwives. He began to look for the cause, reasoning correctly that something was different between ward one and ward two. Among other things, he noted that the midwives had mothers lay on their sides to give birth, while doctors had mothers give birth while laying on their backs. However, having women in ward one give birth on their sides made no difference in the death rate. He searched seemingly in vain for what the cause could be, even instructing a priest to change his routine when visiting the first ward, but to no avail. The answer finally came to him, by way of a tragedy.

Jakob Kolletschka, a fellow doctor and friend of Semmelweis’ accidently cut himself while performing an autopsy on a woman who had died of puerperal fever. He subsequently died, quickly and painfully, exhibiting the same symptoms associated with childbed fever. The cause and effect made plain by the death of his colleague was not lost on Semmelweis. He was now certain that ‘cadaverous particles’ were the cause of puerperal fever and that those particles were transferred from the dead to women who had just given birth. The transfer agents were the doctors themselves, who went from autopsy to delivery room. Midwives never attended to the dead or assisted in autopsies, which only left the doctors as the possible avenue of infection.

The solution to the problem, Semmelweis realized, was to practice rudimentary hygiene after autopsy before going to delivery. He ordered all the doctors under his supervision to wash their hands in chlorinated lime water (calcium hypochlorite solution) to remove the smell of ‘cadaverous particles’. This simple act disinfected the doctor’s hands, but Semmelweis couldn’t have known that.

The death rate in ward one went down to the levels recorded for ward two as a direct result of hand washing.

For the next several years, Semmelweis tried to convince doctors at Vienna General Hospital and across Europe that hand washing prevented deaths. But he couldn’t explain why it worked. Microorganisms hadn’t been discovered yet, and germ theory had not yet been postulated. It didn’t help that Semmelweis lacked tack and diplomacy, alienating many with curt behavior and public insults. Even without Semmelweis’ poor personal relationship skills, most doctors were unwilling to consider the possibility that they could be the cause of so many deaths. Semmelweis was seen as a radical and his idea was crazy. The reflexive reaction to new ideas that contradict established beliefs has come to be known as the Semmelweis reflex, or Semmelweis effect.

The established medical authorities of the time pushed back hard against Semmelweis and his idea, ridiculing him mercilessly as well as anyone that supported him. He was fired from his job at Vienna General Hospital. The stress of being ostracized may have gotten to him, or he may have suffered from a bipolar disorder or a physical malady. His behavior became more erratic and socially unacceptable. He was committed to a mental institution, where he was beaten by the guards for bad behavior. It’s suspected that during the beating he was cut or otherwise somehow received an open wound that became infected. He died two weeks later of sepsis in 1865 at the age of 47.

Within a few years of Semmelweis’ death, germ theory and hand washing were well on their way to wide acceptance. Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis was just a man ahead of his time.

Question of the night: Have you ever been ahead of your time?