Despite the fact that Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had visited President Dwight Eisenhower the previous September, in January, 1960, the relationship between West and East was still extremely tense.

When Eisenhower took office in 1953, his administration’s driving policies were to reduce spending (including Pentagon spending), contain the Soviet Union, and counter the spread of communism. The latter two goals were unchanged from those of the Truman administration. The big change was that while Truman sought to contain and counter with large and expensive land, sea, and air forces, Eisenhower recognized that nuclear weapons were much less expensive to build and maintain than a large standing military.

In a speech on January 12, 1954, Secretary of State John Dulles used the phrase “massive retaliation” to describe the United States’ approach to holding back the Soviets and communism. The era of nuclear deterrence had begun.

An high-tech arms race accelerated with both sides building missiles to augment their nuclear bomber forces. The Soviets launched Sputnik in 1957, providing proof that their missiles, with nuclear warheads, could reach the United States. Whether they could actually build a small enough nuclear bomb on a big enough rocket yet was unproven, but it didn’t matter. The perception in the West was that they could. The space race took off in earnest and with a bang: the Soviets regularly sent satellites into orbit, while the United States regularly blew up our own rockets on the launch pad. The Soviets had not yet put the first man, Yuri Gagarin, in space but would in 1961.

The American public was nervous. A significant number of us had already built backyard bomb shelters. The Office of Civil Defense provided woefully small and under-stocked fallout shelters across the country and taught the masses to “Duck and Cover“. Children were taught to get underneath their desks if the war started during school hours. This was the state of mind of America in 1960.

In the Soviet-occupied Kuril Islands in the eastern Pacific, north of Japan, four soldiers [many sources say they were sailors but they were actually in the Soviet army] assigned to landing craft T-36 were moored in Kasatka Bay at the island of Iturup. The 57 foot craft had two engines but only made 9 knots, maximum speed. In size and appearance, it was similar to a U.S. Navy LCM (Landing Craft Mechanized).

Junior Sergeant [many sources say Master Sergeant] Askhat Ziganshin, 21 years old, was in command. Privates Philip Poplavsky, 20, Anatoly Kryuchkovsky, 22, and Ivan Fedotov, 21, rounded out the crew. Their job was to ferry supplies and munitions from the island stores to large naval vessels anchored offshore. On January 17, 1960, a hurricane caught them by surprise. The winds and waves caused T-36 to break free of its mooring and pushed it out to sea. For the next ten hours, the young men struggled against severe weather to get the small vessel to shore. At least once they struck rocks and sprung a leak in the engine compartment. They were able to plug the hole, but the engines soon ran out of diesel fuel. Their radio quit working or was damaged somehow [again, sources]. Without the radio, they couldn’t inform their base as they were swept out to sea. After the hurricane, a life preserver was found, leading the army to believe the craft and crew had sunk. The search was given up too soon.

The T-36 was not designed for deep water ocean journeys, especially not in heavy seas, but somehow stayed afloat. Eventually the storm moved on and T-36 was left alone to drift, but being January in the northern Pacific, it was very cold. The crew had very little in the way of food and fresh water on board. A loaf of bread, a bucket of potatoes that somehow had been splashed with diesel, a little bit of cereal. They recovered water out of the engine cooling system that was rusty and muddy, but drinkable. They also collected rainwater. Everything was strickly rationed, but it wasn’t enough. They attempted to catch fish every day, but caught not a single one. They resorted to eating anything leather they could find, as well as soap, toothpaste, and tarpaulin boots. They’d been lost at sea now for seven weeks and had drifted 1,000 miles.

The aircraft carrier USS Kearsarge departed Yokosuka, Japan, on March 3, 1960, destination Alameda, California for arrival on or about March 15.

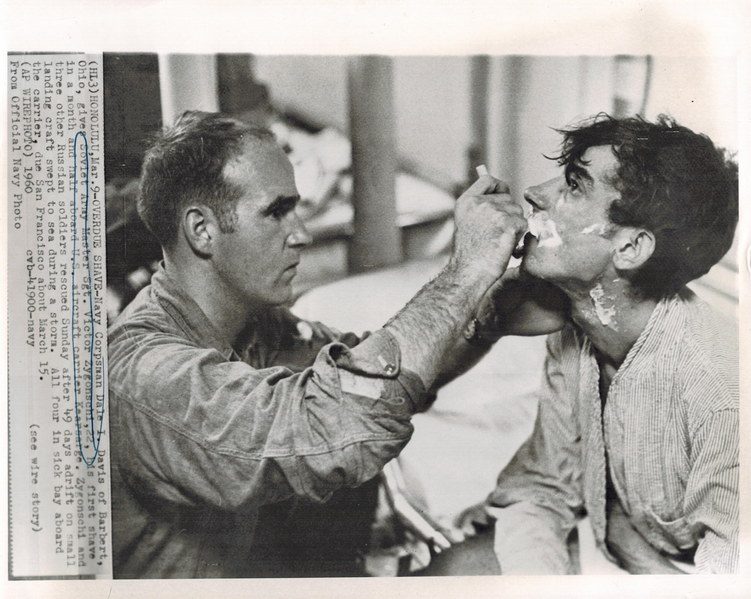

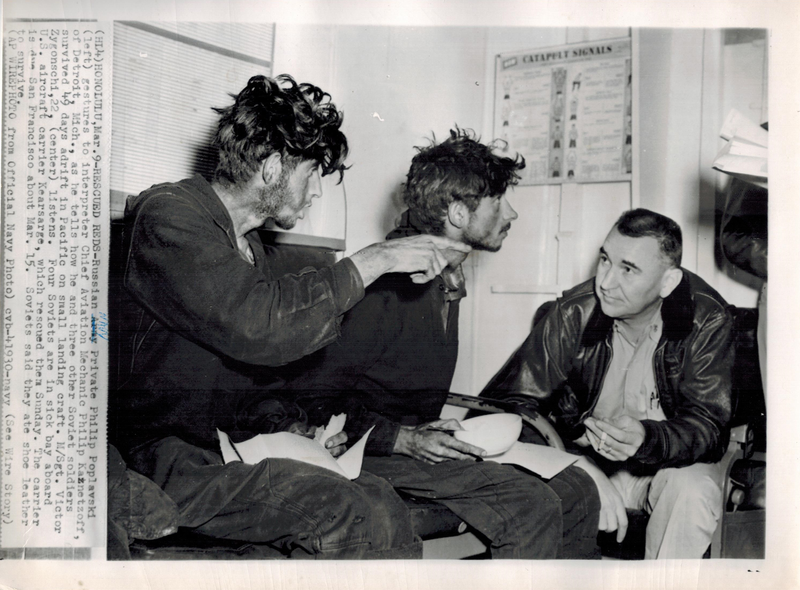

On March 7, 1960, their 49th day adrift, the young men were spotted by a lookout on the Kearsarge. Initially they only wanted supplies, fearing they’d be punished for abandoning T-36 and accepting rescue by Americans. Given a second chance, they relented and were placed in sick bay aboard the carrier where they were given medical attention, water, and small amounts of food to begin with. They also were given haircuts and a shave, and presumably a shower.

One of the Kearsarge crewmembers, Chief Aviation Mechanic Philip Kaznetzoff, spoke enough Russian to act as an interpreter. The Navy was able to learn how the men came to be lost at sea, and communicated that story to headquarters in Honolulu. The story was passed on to the news wire services and became a worldwide frontpage newstory sensation.

In San Francisco, the young Soviet men were treated like honored guests and celebrities, given new suits, $100 spending cash, and the keys to the city. Doctors deemed it unsafe for the men to fly home to the Soviet Union due to their health. Instead, they traveled across the USA to New York, took the Queen Mary to Europe, and were treated like heroes back home in the USSR (0:40):

For a brief shining moment, the kindness of the United States shown to Soviet military men in dire need made the world forget about the Cold War and the possibility of nuclear war.

Question of the night: Choose your preferred scenario in case of being lost: (1) a castaway on an uncharted island in the ocean, (2) in Siberia, (3) in the desert, (4) in the arctic/antarctic.