Luigi di Cesnola is a major figure in American art and somewhat loathed among European historians. While U.S. Consul to Cyprus, the Italian-born art lover excavated – personally or through subordinates – tens of thousands of artifacts from the soil of the Mediterranean country, selling some of them to collectors and museums throughout the world but keeping the bulk of them for the Metropolitan Museum of New York. His efforts simultaneously made him wealthy and slotted him as the first Director of the fledgling museum.

The massive collection – with di Cesnola’s name prominently displayed – remains available for view at the Met, and is the source of most of his contemporary recognition. I would suggest the actions which led to him becoming Consul were more impressive, and an inspirational study in loyalty.

di Cesnola, born in 1833, was a teenager when he fought in the first Italian War for Independence… a war which was lost. After a stint as a soldier in the Crimean War, di Cesnola decided to leave Europe and its continual conflicts. In 1860 he arrived in the United States. Settling in New York, his experience as an officer and his personal magnetism landed him the directorship of a military academy.

When the American Civil War started, di Cesnola was an obvious choice for an officer position. He joined the infantry under the Americanized name of Louie di Cesnola, and quickly rose from Major to Colonel… before being tossed out of the forces for theft.

There was one big issue that the Colonel had with his discharge, and that was his innocence. He protested his removal, and the subsequent investigation demonstrated that he had not stolen the weapons as had been alleged. He was fully exonerated.

The Italian-American officer returned to his Regiment with the intent to resign after a few months. He felt he’d been wronged by his adoptive homeland, but his sense of duty demanded he stay with his troops long enough to demonstrate his devotion to them. Those few months developed into years.

The Colonel’s advancement was hindered due to his loyalty; specifically, his loyalty to General George McClellan. Internal politics is always in play in the military, even during wartime. After McClellan was removed as General-In-Chief, his supporters were expected to shift their loyalties to his replacements. Colonel di Cesnola held to his stated views and was sidelined for it.

Preceding the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station, di Cesnola had enough of being passed over for command, insulted, and treated with contempt. He led his troops to the battlefield, exactly as instructed… but did so by passing directly through an infantry camp which had been erected in their path, rather than suffer the ignominy of being shuttled around a perceived subordinate group and the subsequent belittlement for failing to reach his position in time. Some reports suggest di Cesnola even proposed a duel between himself and another officer following the incident.

Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton personally arrested di Cesnola after his action. It is uncertain as to whether the charges were going to be related to the insubordination or the prospective duel, because fate intervened. On June 17, at the Battle of Aldie, di Cesnola’s men failed to take their position against the Southern enemy. Depending on the recollection it was because they were being poorly commanded or because they staunchly refused to take the field without their Colonel.

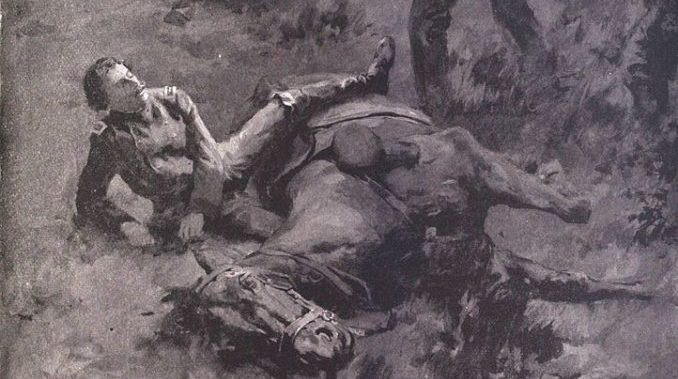

One thing is certain: the regiment was in danger of rout and capture by the enemy. di Cesnola responded in a way that came naturally: despite technically being a prisoner, having been repeatedly humiliated and holding no weaponry, he ran to his troops and rallied them. He charged at the enemy, directing his men to positions where they could best be used. The tide shifted back and forth, and the Colonel was finally pushed back to a position where he could regroup. He summoned what men he had left and prepared to charge again…

… and found Pleasonton in front of him. The Brigadier General informed him that he was no longer under arrest, and handed his sword over to di Cesnola so he would not again charge into combat unarmed.

According to the National Archives, Pleasonton’s words recognized di Cesnola’s heroism. “Colonel, you are a brave man. You are released from arrest. Here is my own sword. Take it and bring it back to me covered in the enemy’s blood. “

For his actions during the battle, di Cesnola was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, but he only collected it after having spent months as a prisoner of war. After the battle was over, the Colonel had remained behind as part of an attempt to help injured Union troops retreat, and he had been captured.

He was eventually traded in a prisoner swap for one of Jefferson Davis’ close personal friends, and the resultant fame from his award led directly to his appointment as Consul to Cyprus.

Question of the night: Have you ever been placed in a dangerous situation because of your friends?