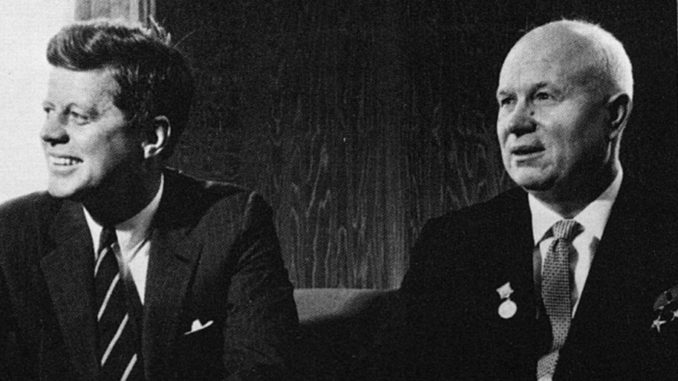

In an essay marking the 50th anniversary of the June 3-4, 1961 U.S.-Soviet Summit held in Vienna, Atlantic Council President and CEO Frederick Kempe discussed Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s brutal effort to seek Soviet advantage. Kempe wrote (Reuters):

As he drove away from the Soviet embassy with Secretary of State Dean Rusk in his black limo, Kennedy banged the flat of his hand against the shelf beneath the rear window. Rusk had been shocked that Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev had used the word “war” during their acrimonious exchange about Berlin’s future, a term diplomats invariably replaced with any number of less alarming synonyms.

In contrast to President Trump’s astonishing demonstration of weakness in Helsinki, President Kennedy refused to yield to the Soviet leader. Nevertheless, perhaps because of Kennedy’s age, the dramatic U.S. setback in the April 1961 “Bay of Pigs” operation (U.S. Department of State) aimed at toppling Havana’s communist regime, or some combination of those two factors, the Soviet leader believed that his American counterpart was weak.

On June 4, the two leaders engaged in a wide-ranging discussion concerning Germany’s and Berlin’s fate. The Soviet leader pressed for a peace agreement that would dramatically advance the Soviet Union’s geopolitical position. The U.S. Department of State’s Memorandum of Conversation noted:

The President continued by saying that the US was interested in maintaining its position in Berlin and its rights of access to that city. He said he recognized that the situation there is not a satisfactory one; he also recognized that in the conversations Mr. Khrushchev had had with former President Eisenhower the term “abnormal” had been used to describe that situation. However, because conditions in many areas of the world are not satisfactory today it is not the right time now to change the situation in Berlin and the balance in general. The United States does not wish to effect such a change. The US is not asking the USSR to change its position but it is simply saying that it should not seek to change our position and thus disturb the balance of power. If this balance should change the situation in West Europe as a whole would change and this would be a most serious blow to the US.

Khrushchev rejected the American President’s explanation and blamed the United States for acting unreasonably:

Mr. Khrushchev said that he was sorry that he had met with no understanding of the Soviet position. The US is unwilling to normalize the situation in the most dangerous spot in the world. The USSR wants to perform an operation on this sore spot—to eliminate this thorn, this ulcer—without prejudicing the interests of any side, but rather to the satisfaction of all peoples of the world. It wants to do that not by intrigue or threat but by solemnly signing a peace treaty.

On the surface, such a stance seemed eminently reasonable. After all, what nation would not want to seize the opportunity to conclude a peace agreement that ends a long-festering dispute?

Actually, the Soviet position was far from benign. Therefore, Khrushchev tried to bait Kennedy into accepting his terms by shifting responsibility for the lack of a peace agreement to West Germany and NATO. The Memorandum continued:

The USSR wants a peace treaty because such a treaty would impede those people who want a new war. Revanchists in West Germany will find in a peace treaty a barrier impeding their activities. Today they say that boundaries should be changed. But if a peace treaty is signed there will be no ground for revision of the boundaries. Hitler spoke of Germanyʼs need for Lebensraum to the Urals. Now Hitlerʼs generals, who had helped him in his designs to execute his plans, are high commanders in NATO.

Khrushchev vowed that the Soviet Union would “sign a peace treaty.” He coupled that promise with a threat:

Mr. Khrushchev continued by saying that he wanted the US to understand correctly the Soviet position. This position is advanced not for the purpose of kindling passions or increasing tensions. The objective is just the opposite—to remove the obstacles that stand in the way of development of our relations and to normalize relations throughout the world. The USSR will sign a peace treaty and the sovereignty of the GDR will be observed. Any violation of that sovereignty will be regarded by the USSR as an act of open aggression against a peace-loving country, with all the consequences ensuing therefrom.

Kennedy, wanting to assess whether the Soviet Union intended to use the peace treaty to swallow all of Berlin raised the question about whether the treaty would “block access to Berlin.” The Soviet leader confirmed that it would. Kennedy then turned down the treaty citing the impact it would have on America’s global position. The Memorandum continued:

If the US were driven out of West Berlin by unilateral action, and if we were deprived of our contractual rights by East Germany, then no one would believe the US now or in the future. US commitments would be regarded as a mere scrap of paper. The world situation today is that of change and no one can predict what the evolution will be in such areas as Asia or Africa. Yet what Mr. Khrushchev suggests is to bring about a basic change in the situation overnight and deny us our rights which we share with the other two Western countries. This presents us with a most serious challenge and no one can foresee how serious the consequences might be…

Khrushchev was taken aback at the U.S. resistance:

Mr. Khrushchev continued by saying that all the USSR wants is a peace treaty. He could not understand why the US wants Berlin. Does the US want to unleash a war from there?

…Mr. Khrushchev continued by saying that if the US should start a war over Berlin there was nothing the USSR could do about it. However, it would have to be the US to start the war, while the USSR will be defending peace.

Following the summit while still perceiving Kennedy to be a weak leader, as Kennedy had feared, Khrushchev proceeded to test the U.S. President. Kempe explained:

A little more than two months after Vienna, the Soviet would oversee the construction of the Berlin Wall. That, in turn, would be followed in October 1962 by the Cuban Missile Crisis. Already in Vienna Kennedy was distraught that Khrushchev, assuming that he was weak and indecisive, might engage in the sort of “miscalculation” that could lead to the threat of nuclear war.

Weakness or perceptions of weakness can invite pressure, tests of strength, and even catastrophe. President Kennedy ultimately passed his Soviet-imposed tests. Over time, the Soviet Union recoiled as the American President demonstrated his willingness to persevere in defense of American interests and allies regardless of Soviet pressure.

The lesson of the 1961 Summit has relevance today. In the wake of President Trump’s historical exhibition of weakness in Helsinki, Russia will very likely seek to consolidate its position and press for additional advantages across the geopolitical stage. In doing so, Russia will likely try to exacerbate the fresh divisions President Trump created between the United States and its NATO partners, both at the G-7 and NATO Summits.

How will President Trump respond to his upcoming test(s) from Moscow? One can be certain that the opportunistic Russian President won’t remain idle following his decisive “win” at Helsinki.