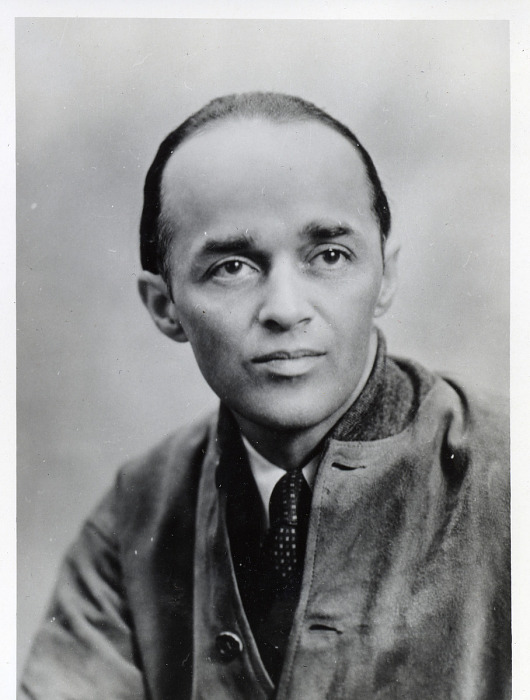

James Herbert Brockett was born in Kansas, 1893, and raised in Omaha, Nebraska, by adoptive parents, the Knights, who called him Jack. He was a skinny boy who remained very thin and slight as an adult. Upon coming of age he joined the US Army, where he became a Military Aviator, Aviation Section, Signal Corps, and served as a pilot instructor during the First World War. Lieutenant Knight was discharged from the Army in 1919, afterwhich he found work as an airmail pilot.

Airmail service was in its infancy. The Post Office Department (an earlier name for the USPS) was very interested in developing faster cross-country transport of letters and had begun experimenting with delivery of mail by aeroplane in 1911. Railroads had carried mail all across the country for decades, but it took several days for mail to reach its destination by train.

At that time there was very little aviation infrastructure. Other than an unreliable compass in the aircraft cockpit and auto club road maps, pilots had no navigation aids. They relied on spotting landmarks and other visual cues on the ground such as bodies of water, a technique called ‘dead reckoning’. There were very few airfields, mostly found only in larger cities. There were no such things as landing lights, either at the airfield or on the airplane. Not even the rudimentary instrument panels were lit. Flying at night or in bad weather, then, was out of the question.

The first transcontinental air route (PDF 1.59MB), from New York to San Francisco was initiated in 1920. Because aircraft were necessarily limited to daylight hours (and good weather) trains still carried the mail when planes were grounded. For example: a plane would carry the mail during the day on the first leg from New York to Cleveland; Evening came and the mail was transferred to rail; Overnight a train carried the mail from Cleveland to Chicago where it was transferred to a fresh waiting plane and pilot, who took off early in the morning headed for Omaha, and so on. By using air service, the Post Office Department was able to shorten the time it took to move mail from San Francisco to New York (or vice versa) by 22 hours, unless the weather was bad.

Unfortunately, weather reporting and forecasting was not anywhere near as good then as it is now. Airmail pilots who encountered bad weather could not see the ground and became lost, at best, or crashed. A number of pilots had been killed in this way, and expensive aircraft had been destroyed. Congress was not happy, and were debating whether to even continue funding the service.

The Post Office Department decided that a demonstration of airmail’s potential was needed. No trains would be involved. Aircraft would fly the mail from one station to the next, where a fresh pilot and plane would take the mail on the next leg, Pony Express style. Winter was the worst time of year to attempt a nightime transcontinental airmail relay, but congress was poised to axe the service. None of the pilots had much, if any, nighttime flying experience. Plus, they flew open-cockpit aircraft which were even colder on a winter night than during a winter day, if you can imagine. The service threw a Hail Mary.

On the morning of February 22, 1921, two aircraft left New York, bound for San Francisco. Two more aircraft departed San Francisco, bound for New York. One westbound plane iced up and was forced down in Pennsylvania. An eastbound plane crashed outside of Elko, Nevada, killing the pilot. Another westbound plane reached Chicago but could go no further due to a snowstorm.

Jack Knight waited in North Platte, Nebraska, to fly his leg of the eastbound relay to Omaha. Flying a different leg several days prior, he had crashed into a mountain peak in the Laramie Mountains, in Wyoming, suffering a broken nose and a concussion. Now he was about to embark on his first night flight. The incoming airmail arrived after dark, and Jack took off with it toward Omaha.

Post Office Department employees and private citizens marked Jack’s route with bonfires. However, the weather near Omaha was bad, making his first night landing even more harrowing. Once on the ground though, he learned the pilot that was assigned to fly the next leg wasn’t in Omaha. Without a pilot to fly the Omaha to Chicago leg, the demonstration to prove the value of airmail would fail, and the service would be defunded. Despite being cold, tired, and hungry, and never having flown that leg before, Knight volunteered to fly.

Again, bonfires helped him find his way across Iowa where he intended to land at Iowa City to refuel. However, employees there thought the flight had been cancelled due to the bad weather and went home, so there were no fires to mark the airstrip. Although Jack had never seen that airfield before, he managed to find it. A night watchman heard his plane and lit a flare – just enough light to allow a landing. After refueling, Knight crossed Illinois to the Chicago airmail station where journalists who had heard of his daring feat were waiting for him. The airmail was transferred to the next plane which left immediately for Cleveland to meet the final leg to New York.

Jack’s courageous effort allowed the transcontinental airmail demonstration to set a new record of just 33 hours and 20 minutes to move mail from one coast to the other. The press dubbed him, “the hero who saved the airmail”. The positive embrace by newspapers and the public convinced congress to increase airmail service funding to $1.25 million dollars. Most of that money was invested in aviation infrastructure to improve day and night navigation, airport lighting, beacons, radios, and a host of other improvements.

This little-known bit of history has huge implications. By 1926, the Post Office Department began contracting out airmail service to private aviation companies – the first airlines. The airmail contracts helped fledgling airlines to survive even during the Great Depression when air passengers were few. Because there were airlines, aircraft manufacturing companies had customers to buy new aircraft. A healthy and innovative aircraft industry provided the United States with the engineering and technical skills to build advanced aircraft that would be so critical during the Second World War. If congress had decided not to further fund the airmail service, there would have been no airmail contracts to support startup airlines. No airlines, no aircraft industry.

Jack Knight was not only “the hero who saved the airmail”, he was the hero responsible for America being prepared for an air war against tyranny.

Question of the Night: What’s your favorite season, Spring, Summer, Fall, or Winter, and why?