Joseph R. Beyrle [buyer-lee] was born August 8, 1923, in Muskegon, Michigan, the middle child of seven. His parents were first-generation Americans, themselves children of German immigrants. Some of his earliest childhood memories included standing in Depression-era food lines with his father. After high school, he could have gone to Notre Dame on a basketball scholarship. Instead of starting college in September of 1942, he joined the US Army and volunteered for the paratroops.

Assigned to the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), he was sent to Camp Toccoa, Georgia, for training. The mini-series “Band of Brothers” focused on Easy (E) Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th PIR. Beyrle was assigned to Item (I) Company, 3rd Battalion, 506th PIR. The 506th was one of four regiments that were part of the famous 101st Airborne Division, “Screaming Eagles”. Regardless of battalion or company, they all had to run Mt. Currahee, “three miles up, three miles down”. His fellow paratroopers gave him the nickname “Jumpin’ Joe”. Following completion of training, the 506th was sent to England to prepare for the Normandy Invasion.

In addition to infantry and parachute training, Beyrle specialized in radio communications and demolition. This meant he would be among the first paratroopers dropped into Normandy on D-Day, assigned to blow up electric power stations in order to disrupt German defenses.

As with all other C-47s on D-Day, Sergeant Beyrle’s aircraft was targeted by heavy anti-aircraft fire. As a result, the plane was too low and too fast and not over the assigned drop zone when the green light flashed on and the paratroopers in his stick jumped into the night. Germans on the ground fired at him as he descended onto the steep roof of the church in Saint-Côme-du-Mont. A German soldier in the church bell tower kept firing at Beyrle as he slid down the roof and landed hard on the ground below. Shedding his parachute, he disappeared from view.

Paratroopers are supposed to meet and regroup on the ground, but Beyrle met no one. Studying his map, he figured out where he was and proceeded to his first objective, a power station, which he destroyed with explosives. He then moved on to other targets, doing whatever damage he could until captured. His uniform and dogtags were taken from him, and Beyrle was sent to a POW camp. The US Army later found a dead German soldier wearing Beyrle’s uniform and dogtags, assumed it was him and pronounced him dead. Naturally the government notified his parents, and the local priest held a funeral mass for him.

Discontent to be a POW, Beyrle and a couple of other prisoners managed to escape and hitched a ride on a freight train. Apparently they were direction disoriented when they caught the train, which took them to Berlin. The Gestapo got hold of them, complete with beatings, torture, and a threat of execution. Fortunately, the Wehrmacht intervened and returned Beyrle and his fellow travellers to a different POW camp, Stalag III-C in Alt Drewitz, located in the east of Germany in what is now Poland.

In January, 1945, as the Soviet Army approached the POW camp, Beyrle and two others made a daring plan to escape and join up with Russian forces to fight the Nazis. They hid themselves inside barrels on a horse-drawn wagon. Somehow the wagon was jarred or damaged, the barrels rolled out and the escapees were seen. Guards fired on the three, killing his friends, but Beyrle got away and headed east. Eventually he bumped into the advancing 1st Battalion, 1st Guards Tank Brigade, Red Army, which was commanded by Alexandra Grigoryevna Samusenko, a woman and a tank officer.

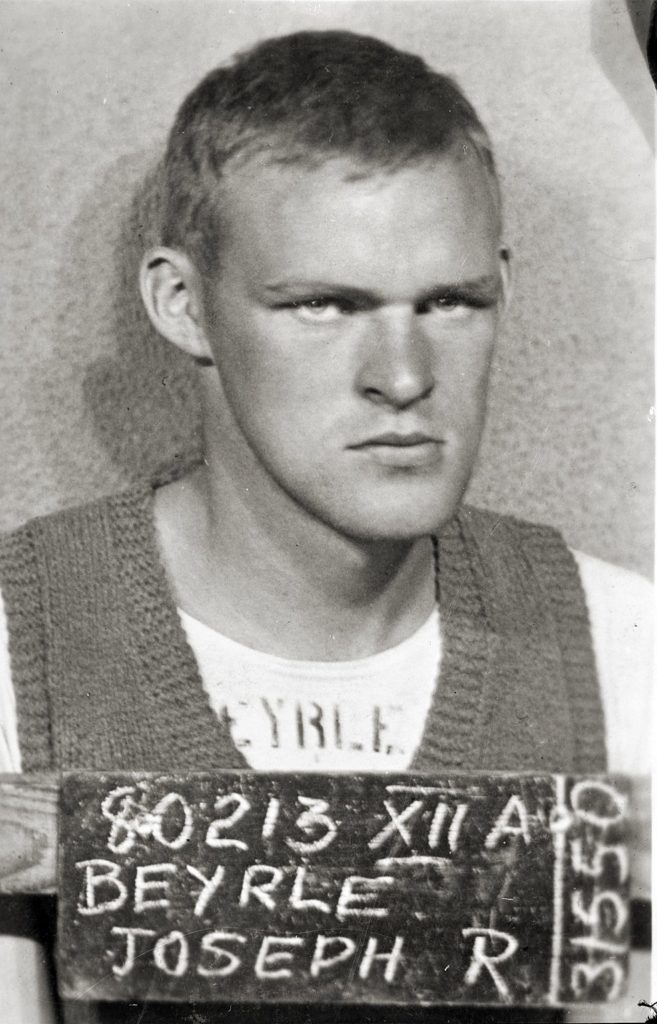

Beyrle convinced her that he was an American soldier and requested her permission to fight with her battalion, which she granted. Weeks later, the tank battalion came upon Stalag III-C, the POW camp Beyrle had barely escaped from with his life. Once the camp was liberated, he broke into the camp administrative offices and found documentation along with his POW photo. He could now prove who he was.

In early February, Stuka dive bombers attacked the 1st Battalion, injuring Beyrle. He was sent to a field hospital near the front. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, Hero of the Soviet Union, victor over the Japanese Imperial Army at Khalkhin Gol, and commander of all Soviet forces on the Eastern Front stopped to visit the wounded. Zhukov took an interest in the American, and provided Beyrle with documents that allowed him to travel anywhere and anyplace under Soviet control. Once he recovered well enough to leave the hospital, Beyrle went to the American Embassy in Moscow.

Diplomatic staff at the embassy treated him with suspicion, since he was known to be dead, and placed him under guard of the Marines. Fingerprints eventually pursuaded the skeptical American officials.

Returning home, he married JoAnne Hollowell in 1946. They were married by the same priest that had said mass for him two years prior. They had three children. His son Joe Beyrle Jr., served in the 101st Airborne during Vietnam. His other son, John Beyrle, became a diplomat and served as ambassador to the Russian Federation from 2008 to 2012.

Joseph Beyrle is the only American known to have served with both the US and Soviet armies.

Later in life, Joe became involved in organizing reunions of the 101st. After one such reunion in Toccoa, Georgia, Jumpin’ Joe passed away peacefully in his sleep on December 12, 2004, at a hotel near Camp Toccoa and Mt. Currahee. He was 81 years old.

Question of the Night: Why doesn’t Hollywood make movies about men (and women) like this?

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.